|

The

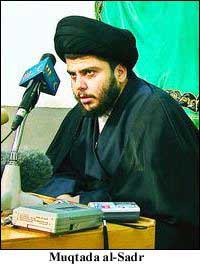

Army's powerful 1st Armored Division is proclaiming victory

over Sheik Muqtada al-Sadr's marauding militia that just

a month ago seemed on the verge of conquering southern

Iraq. The

Army's powerful 1st Armored Division is proclaiming victory

over Sheik Muqtada al-Sadr's marauding militia that just

a month ago seemed on the verge of conquering southern

Iraq.

The Germany-based division defeated the

militia with a mix of American firepower and money paid

to informants. Officers today say "Operation Iron

Saber" will go down in military history books as

one of the most important battles in post-Saddam Hussein

Iraq.

"I've got to think this was a watershed

operation in terms of how to do things as part of a counterinsurgency,"

said Brig. Gen. Mark Hertling, a West Point graduate and

one of two 1st Armored assistant division commanders,

in an interview last week as he moved around southern

Iraq. "We happened to design a campaign that did

very well against this militia."

When

the division got word April 8 that Sheik al-Sadr's uprising

meant most 1st Armored soldiers would stay and fight,

rather than going home as scheduled, it touched off a

series of remarkable military maneuvers. When

the division got word April 8 that Sheik al-Sadr's uprising

meant most 1st Armored soldiers would stay and fight,

rather than going home as scheduled, it touched off a

series of remarkable military maneuvers.

Soldiers, tanks and helicopters at a port

in Kuwait reversed course, rushing back inside Iraq to

battle the Shi'ite cleric's 10,000-strong army. Within

days, a four-tank squadron was rumbling toward the eastern

city of Kut. And within hours of arriving, Lt. Col. Mark

Calvert and his squadron had cleared the town's government

buildings of the sheik's so-called Mahdi's Army.

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Martin E. Dempsey,

1st Armored commander, huddled with Gen. Hertling and

other senior aides to map an overall war strategy. The

division would shift from urban combat in Baghdad's streets

to precision strikes amid shrines of great religious significance.

Hunting the enemy in tight city streets

broadened to patrolling a region the size of Vermont.

Gen.

Dempsey first needed the locations of Sheik al-Sadr's

rifle-toting henchmen. Average Iraqis, fed up with the

militia's kidnappings and thievery, quickly became spies,

as did a few moderate clerics who publicly stayed neutral. Gen.

Dempsey first needed the locations of Sheik al-Sadr's

rifle-toting henchmen. Average Iraqis, fed up with the

militia's kidnappings and thievery, quickly became spies,

as did a few moderate clerics who publicly stayed neutral.

Once he had targets, Gen. Dempsey could

then map a battle plan for entering four key cities --

Karbala, Najaf, Kufa and Diwaniyah. This would be a counterinsurgency

fought with 70-ton M-1 Abrams tanks and aerial gunships

overhead. It would not be the lightning movements of clandestine

commandos, but rather all the brute force the Army could

muster, directed at narrowly defined targets.

Last week, Sheik al-Sadr surrendered.

He called on what was left of his men to cease operations

and said he may one day seek public office in a democratic

Iraq.

Gen. Hertling said Mahdi's Army is defeated,

according to the Army's doctrinal definition of defeat.

A few stragglers might be able to fire a rocket-propelled

grenade, he said, but noted: "Do they have the capability

of launching any kind of offensive operation? Absolutely

not."

The division estimates it killed at least

several thousand militia members.

Gen. Dempsey designed "Iron Saber"

based on four pillars: massive combat power; information

operations to discredit Sheik al-Sadr; rebuilding the

Iraqi security forces that fled; and beginning civil affairs

operations as quickly as possible, including paying Iraqis

to repair damaged public buildings.

"As soon as we finished military

operations, we immediately began civil-military operations,"

said Gen. Hertling. "We crossed over from bullets

to money."

The strike into Kut was followed by an

incursion into Diwaniyah. Then an 18-tank battalion entered

Karbala, a holy city where precision operations were needed

to spare religious shrines. Then soldiers moved into Najaf

and Kufa, where Sheik al-Sadr was hiding out and where

about 3,000 of his fighters occupied government buildings,

mosques, amusement parks and schools.

"We were going from outside in to

get this guy," Gen. Hertling said. "We had to

go after them one city at a time."

|